How language evolves to make meaning in an ever-changing world.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me. A well-known childhood taunt hurled back at a schoolyard bully. The intent: Words cause no harm. The reality: The lesson doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Whether words are deliberately thrown or carelessly dropped, they do have the power to injure. But they also have the power to inspire and move worlds. It’s all in how they are wielded.

Consider these quotes drawn from great speeches: “I have a dream,” “Tear down this wall!” “¡Sí Se Puede!” and “We are talking about feminism.” Phrases such as these, uttered by exceptional orators at precisely the right moments in history, have pushed for changes that propelled societies toward progress.

“Movements are started based on language and its phrases, and thus language can then be a powerful rallying call for change,” said Afua Hirsch, professor of journalism.

Sarah Banet-Weiser, professor of communication, adds that language not only moves worlds but fundamentally shapes them. Words matter, and they matter differently depending on history, culture and politics. “They move through time, taking on nuance and meaning in different cultural environments,” she said. “And while language has gone through similar sorts of traveling during different historical moments, when I think about where we are today and how we are communicating, it feels very urgent.”

In a year marked with a global pandemic, a pressing demand for racial justice and a determination to advance gender equity, understanding how words continue to be defined and redefined — combined and recombined — has never been more critical. Communicators like Banet-Weiser and Hirsch are among those across USC Annenberg who are deeply invested in exploring not only the weight our words carry, but also how they can serve as a catalyst for transformation.

Miss Rona

“Quarantini,” “doomscrolling,” “zoombombing”: familiar words fused to form new ones this past year as people sought novel terminology to describe life amid a global pandemic. “Pandemic” itself was named Merriam Webster’s Word of the Year.

While language is a tool to communicate facts about the COVID-19 crisis, it has also been a mechanism to challenge this very same information. This past summer, communication doctoral students, working with Assistant Professor of Communication Cristina Visperas, convened over Zoom to investigate the phenomenon: “What do viral vocabularies do besides communicate?”

“We wanted to dig deeply into the media around the pandemic and look at the language from a critical perspective to understand what exactly was going on and how people were making meaning out of it,” said Himsini Sridharan, a first-year doctoral student.

Take “viral” and “virus,” for example.

“You’re in the midst of this pandemic, you’ve got the public health layer on this, along with a challenging information environment where a lot of people are concerned about viral misinformation,” Sridharan said. “So, you’re dealing with a virus and you’re dealing with viral information about a virus. Where are the connections between those meanings coming from, and are they actually useful in this moment, or is this moment showing us how they break down?”

Sridharan explained that one of the group’s focuses is exploring the adoption of monikers and nicknames for the coronavirus, such as “Miss Rona,” “Aunt Rona” and “China virus.”

“Miss Rona was a term embraced on Twitter by Black and queer communities as a way for these groups to identify and own the virus in a language that represents them,” she said. “It is these slippages that emerge around words from one community to the next, especially in a moment of crisis, that strengthen and crystalize our level of questioning around meaning.”

Brian Spitzberg, who earned his doctoral degree in communication from USC Annenberg in 1981, is also focusing on the term “China virus” and its Orwellian underpinnings as a way to examine how language can influence our understanding of reality. “Language, broadly speaking, does not determine or create reality, but it can significantly shape our perception of it,” he said.

“There’s a growing dread I have that we are experiencing a much-amplified form of 1984,” Spitzberg said, referring to George Orwell’s dystopian novel. “This notion of Newspeak and government control and/or political control of language is increasingly shaping our attitudes in ways that are hard to distinguish from propaganda.”

To that point, he is concerned about the degree to which any one leader has a megaphone. “Whoever is in the White House has the ability to shape language use in ways that will increasingly be focus-grouped and emotion-dialed to determine the best ways of managing the public mind,” he said.

Spitzberg began pursuing this line of research while at USC Annenberg and has since written dozens of articles and books exploring the dark side of communication, looking at threats, conflict and coercion.

Now the Senate Distinguished Professor of Communication at San Diego State University, Spitzberg is delving into COVID-19 conspiracy theories. He notes that a rumor surfaced earlier this year that the virus was “lab-engineered,” which led conspiracy theorists to begin calling the virus a “bioweapon.”

“When a word like ‘bioweapon’ enters the Twittersphere,” Spitzberg said, “it becomes significant in the way in which it then evolves this theory into broader narratives.”

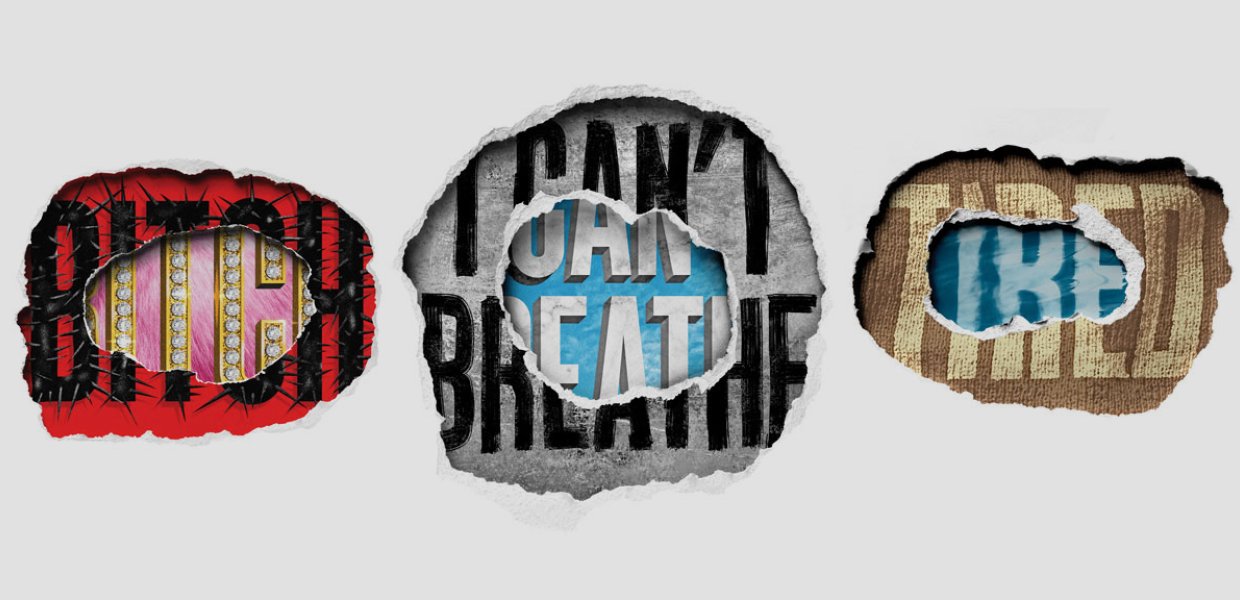

I can’t breathe

While this past year was filled with new words created to make sense of a moment, it was also filled with familiar phrases imbued with new meaning and perspectives.

“I can’t breathe” was one of them.

“I can’t breathe” was repeated by Eric Garner 11 times on July 17, 2014, as he was put in a lethal chokehold by New York City police. On May 25, 2020, George Floyd uttered the same words as he pleaded for his life with Minneapolis police. The words, “I can’t breathe” exploded over the summer and become a rallying cry in protests against police brutality across the world.

Pamela Perrimon noted that the “I can’t breathe” phrase rooted in the Black Lives Matter movement was also embedded in the public health domain, referencing those suffering from a respiratory virus that compromised the ability to breathe. “They felt undeniably connected,” said Perrimon, a second-year doctoral student who also worked on the Viral Vocabularies project.

She went on to add, “On top of this we had another layer of protests we were watching in the media — of people refusing to wear a mask and co-opting the ‘I can’t breathe’ phrase for themselves. This language becomes a way to communicate about the crisis, but it is also a way to argue about information and expertise, politics and responsibility, and even who has the right to breathe.”

Sridharan added, “Those of us on the project wanted to think through these particular terms from a very critical perspective to figure out what they tell us about the broader systems of inequality and exploitation.”

Bitch

“There are times when we don’t have words to explain the moments we are in,” Banet-Weiser said. “So, we invent new words, or we take old words and give them new meaning. This is how we wrestle with language to have it better represent ourselves and our worlds.”

Words such as “bitch,” for instance. Bitch can be used in a derogatory manner to insult and demean women. But Banet-Weiser asserts that words like this can also be reclaimed, recombined and redefined — like “boss bitch” or “bad bitch” — to create a shield against the original intent.

“Words are not neutral,” she said. “Language is the way in which a community is going to say, ‘I’m not going to let you create my world using your words. I’m going to create it myself and give it my own definition.’”

This flipping of the power structure of language around female empowerment is not a new area of research for Banet-Weiser. For the past 20 years she has studied — and taught — gender and media and has seen how young women have positioned themselves in relationship to the word “feminism.”

“It used to be, ‘I’m not a feminist. Yes, I believe in equality, but I’m not a feminist,’” she said. “For my students, feminism was definitely the ‘F’ word. Then, with the onset of Instagram around 2013, I noticed how young women started to embrace more aspirational feminist messages — posting images that dial into body positivity and repurposing words such as ‘nasty’ and ‘bitch.’”

The challenge, though, according to Banet-Weiser, is that these expressions of feminism tend to be more superficial, relegated to social media memes and hashtags, rather than tied to policy and laws designed to create real systemic change for women seeking gender equity.

“It isn’t until we move these ideas beyond the circulation of social media, beyond the visibility they get through those platforms, that any real structural grounding can occur,” she said.

Professionalism

Words like “professionalism,” while seemingly innocuous compared to “bitch,” can also be loaded with complexity.

Authoring a chapter for the book Pretty Bitches, Hirsch chose the word “professionalism” as a way to dive into the preconceptions around who is deemed a professional and how the centuries-old definition has been weaponized against women — particularly women of color.

Born in Norway to a white British father and a Black Ghanaian mother, Hirsch decided early on to pursue a career that would make her family proud. After initially working for an NGO, she went on to earn a law degree, becoming a barrister in England.

She recalls, however, that the image of what a lawyer is supposed to look like was immediately challenged when her “Afro curls” didn’t fit properly into the horsehair wig she was required to wear.

“Women are disadvantaged by ideas of the ‘professional’ before we even walk in the door,” she writes. “To be truly professional is to conform to the ideal on which the word profession is based: an elite white man.”

Hirsch maintains that women are constantly required to alter their clothing, jewelry and footwear to better acclimate to societal models of how one should look in any given profession.

“I spent years ironing my hair and learning how to mimic the behaviors, norms and ideals of whiteness,” she said. “Even when I left law and pivoted to working as a television journalist, I was told that my legs were too muscular for TV and my Afro took up too much of the screen.”

Ultimately, Hirsch realized she no longer wanted to participate in an establishment that prevented her from disrupting the status quo and is now an educator and a documentary filmmaker.

“I became very interested in how I could use my education and my perspective to challenge these perceptions rather than repeat the same patterns I’ve seen previous generations play out,” she said.

Under-resourced

As the marketing communication manager at the National Health Foundation (NHF), Stephany Rodas agrees that words have the ability to influence behavior and outcome. “In order to create environments where individuals feel welcome and appreciated, we have to be very intentional with our language,” she said.

Rodas adds that the NHF, which has been serving Southern California for the past 40 years, has been even more comprehensive in its messaging this past year. They created an inclusive guide to language that is given to new hires and formed a JEDI council — justice, equity, diversity and inclusion. Given the organization’s mission to address the root causes of health disparities in local communities, setting the right tone in their communication is imperative.

Another word switch that was implemented recently was moving away from “underserved” to “under-resourced,” explains Rodas, who earned a master’s degree in strategic public relations in 2018. “When you read the word ‘underserved’ quickly, it looks like ‘undeserved,’ and that is not what we are trying to express.”

As a woman of color, Rodas recognizes her own privilege and acknowledges the importance of educating herself and having honest conversations about race with those in her company and in the community. This type of work, she believes, is necessary to make sure that any internal communications or tweets meant for the public are as inclusive as possible.

“We’re learning — observing shifts in language — and adapting to make sure people, especially those who are most vulnerable, get the most accurate information possible to make the best choices possible,” she said.

Tired

Health communication scholar Robin Stevens’ research is similarly focused on listening closely to the type of language formed within specific communities. A pioneer in the emerging field of digital epidemiology, Stevens uses digital data like social media posts to investigate Black and Latinx youth well-being, sexual health, mental health and substance use.

One of the studies Stevens conducted before arriving at USC Annenberg this Fall was focused on studying depressive language that Black youth use on Twitter. Bridgette Brawner, the co-principal investigator on the project, flagged the word “tired,” indicating that it came out of a study she had conducted designed to address the role of mental illness and emotion regulation in Black teens in Philadelphia. She suggested Stevens add it to her list.

“We then used those insights in developing the classifier — the types of words we are going to look for — as we identified depressive language in social media posts,” Stevens said. She added that words like “tired” or “mad,” used by Black youth to indicate they are depressed, wouldn’t have been included in the DSM-5, a catalogue of mental health disorders created by psychiatrists. Stevens notes that most of the lexicons created to describe mental health afflictions are built on white populations, which is why the work her group does is so necessary.

“So, if we mischaracterize an entire population based on a faulty assessment, we miss critical opportunities to intervene,” she said. “By targeting youth in these digital neighborhoods and their corresponding vocabularies, we’re better able to identify and implement effective public health interventions that allow minoritized youth to thrive.”

People have always used language to make sense of their worlds, and, according to USC Annenberg experts, that isn’t changing. A single word can change a story. Language can create community, solve problems and define the identity and character of a society.

“Having a language is not in itself the work of creating change, but it definitely helps structure your cognitive world in a way that allows you to navigate the change that needs to happen,” Hirsch said. “Language is really important, both in our own understanding and our ability to communicate and find solidarity with others.