The world of sports communication and journalism responds to COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter.

In March 2020, Cooper Goldie was certain that The Players’ Tribune was faced with the biggest sports story in generations: the shutdown of nearly all organized sports under the shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With the abrupt suspension of play, uncertainty and fear gripped the sports world. “We were like everyone else: confused and worried,” said Goldie, who earned his bachelor’s degree in communication in 2014.

Yet, despite games and matches being shut down, Goldie added, the Tribune’s model has always been based less on the games themselves, and more on the humanity of the sports stars who write for the publication. Founded six years ago by New York Yankees Hall of Famer Derek Jeter, The Players’ Tribune features first-person stories written by athletes. “It’s a platform for them to connect directly to both their fans and a larger audience,” said Goldie, who works in athlete marketing and team relations for the site.

“As the grim reality sank in that this virus would prevent sports from being played for a matter of months rather than weeks, we started to see more and more athletes wanting to share their thoughts and experiences about what they were going through,” he said.

Goldie and his colleagues quickly organized this flood of COVID-related ideas into a new section called “The Iso,” where athletes could share first-person stories about being quarantined at home. For example, the NBA’s Kevin Love discussed his mental health struggles and the WNBA’s Jewell Loyd encouraged readers to “flatten the curve.”

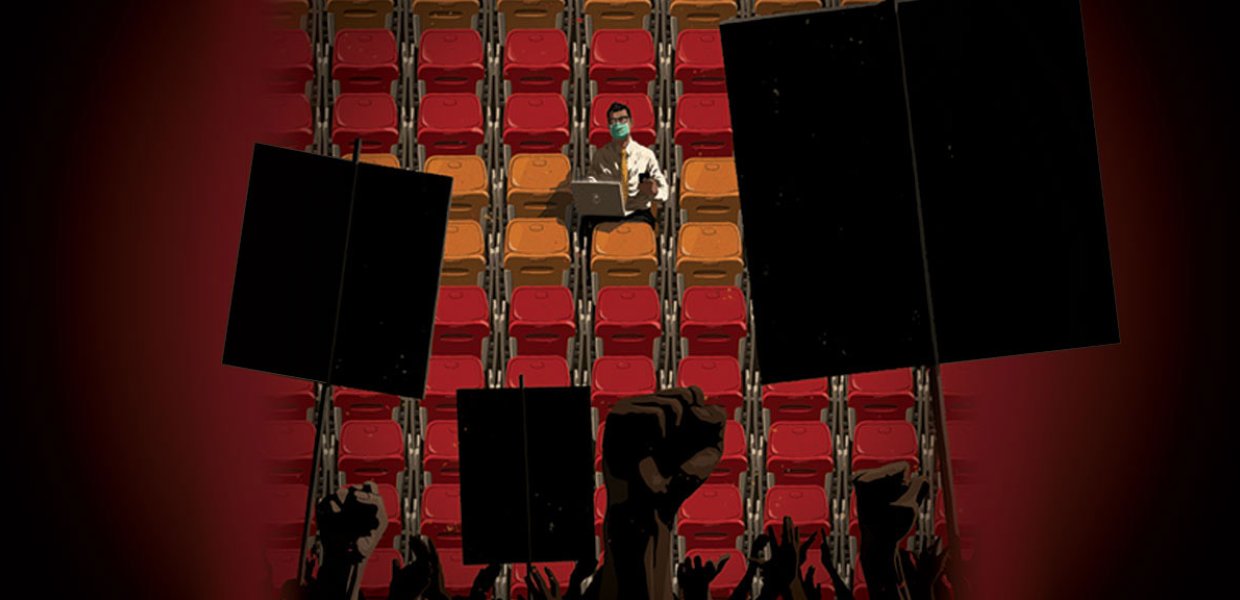

Just as The Players’ Tribune, other sports media outlets, and the teams and leagues themselves were beginning to come to terms with what sports might look like during the pandemic, George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police on May 25. The subsequent mass protests in multiple U.S. cities against police brutality radically shifted the conversation from COVID-19 protocols to the ongoing scourge of racial injustice in America. With many professional athletes putting themselves on the front lines of this movement, the leagues were now faced with a broad-based activist reality among their players and fans that was impossible to ignore.

Goldie says the protests sparked another surge in athletes approaching the Tribune looking to tell stories about their lived experiences of racism. “It was a special moment,” Goldie recalled. “With the sports world stopped, these athletes who we idolize wanted to do the work, to lend their voice, to tell you to go out and vote, to condemn what was happening.” The Tribune created another series called “Silence is Not an Option,” in which more than 35 athletes shared their stories, including WNBA star A’ja Wilson’s “Dear Black Girls” and NBA legend Bill Russell’s “Racism Is Not a Historical Footnote.”

As leagues, teams and individual athletes respond to these new realities, the ways in which they are communicating their responses, and how the media covers those choices, are resonating across all of USC Annenberg’s disciplines. Throughout both the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement, USC Annenberg alumni, students and faculty have been key chroniclers and drivers of how the narrative of the sports world unfolds.

“I think it’s a really fascinating moment,” said Ben Carrington, associate professor of sociology and journalism. “In the late ’60s, we had what some refer to as the rise of consciousness amongst Black athletes. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, Muhammad Ali, and a whole range of athletes were using their platforms to protest racial injustice. It appears that we are in a similar moment right now.”

The pandemic and racial-justice crises created daunting challenges for lead communicators working with teams and leagues, including Karen Goodheart, vice president of marketing and partnership activation for the Los Angeles Galaxy of Major League Soccer.

“Sports teams essentially are a channel for communication,” Goodheart said. “When you have a large, passionate audience, you have the opportunity to communicate in a different way, and I think that’s special. Sports is about so much more than what happens on the field.”

She remembers exactly when the COVID-19 pandemic changed her world.

“On March 12, we were supposed to be in Miami to play our first game against the new club there,” said Goodheart, who earned her bachelor’s degree in public relations in 2011. “We were leaving the office on March 11 and all of this COVID information was coming out, and we just weren’t sure what was going to happen. So, instead of getting on the flight, I went home — and that was my last day in the office until very recently.”

The following weeks, Goodheart says, were a blur of conference calls and Zoom meetings as the MLS began to learn more about the virus and started to plan how — and when — their teams could safely return to the pitch. In these remote meetings, many with team sponsors, they were forced to grapple with how to balance the literal health of their players, personnel and fans with the financial health of the league and its teams.

With the pandemic continuing to soar and play still shut down, the protests that followed in late May and into the early summer created another pivotal moment for teams and leagues. Goodheart says that, for both the MLS in general and the Galaxy in particular, supporting the Black Lives Matter movement was consistent with their long-held values.

“Figuring out our messaging wasn’t difficult,” she said. “It’s pretty clear what was right from the team’s point of view.”

The MLS eventually returned with a tournament starting on July 8 called “The MLS is Back” at the ESPN Wide World of Sports complex in Orlando. They were without fans, creating a “bubble” of players, coaches and support personnel who were rigorously tested for COVID-19 and kept in quarantine. The games featured powerful pregame tributes to George Floyd and social justice messages printed on players’ jerseys.

“Especially in times when the world is uncertain and scary and difficult, sports can bring a level of comfort and passion to people that is so important,” Goodheart said.

By August, the MLS, NBA and Major League Baseball were playing again — albeit in empty stadiums and arenas. Then on Aug. 23, police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, shot Jacob Blake, an unarmed Black man, in the back.

As athletes reacted to this latest atrocity, the NBA’s response was the most dramatic: On Aug. 26, the Milwaukee Bucks refused to come out of the locker room for their playoff game, leading to the league’s postponement of all playoff games for several days.

At an Oct. 5 virtual event in the Annenberg Intelligence series hosted by Dean Willow Bay, sophomore journalism major Reagan Griffin, Jr. had a chance to ask NBA All-Star player Chris Paul about that day.

“Aug. 26, 2020, that’s a date for the history books,” Griffin said. “That’s when Sterling Brown and the Milwaukee Bucks made the decision: ‘We’re not going to play tonight. We’re going to strike.’ Walk us through your role.”

Paul, who is also the president of the National Basketball Players Association, answered, “We were pulling into the arena, and that’s when my phone started going crazy. As a brotherhood, when we saw what Milwaukee did, it was like, ‘We stand with them.’ And the next thing I tried to do was, make sure we had a meeting. And I’m grateful, because I feel like it’s a turning point in our league; a lot of guys spoke in that meeting who maybe wouldn’t have spoken.”

Griffin’s question to Paul stands in USC Annenberg’s long tradition of providing networking opportunities as one way to train top sports journalists.

Annenberg Media, the student-led media organization, which was also remote at the time, reacted to the Black Lives Matter movement by posting a statement of support on its homepage, and also ran several essays by students and recent alumni addressing issues of racial justice. Griffin, who is Black, wrote a piece for Annenberg Media titled “A Letter to My White Friends,” directly and forcefully addressing white sports fans’ lack of willingness to engage with what Black athletes — and Black sports journalists — were telling them about the realities of racism in the United States. The essay was also published on the online sports magazine The Undefeated.

“I’ve had conversations with Black journalists who told me that there are certain things they’ve had to hold back on over the course of their careers,” Griffin said. “They had to swallow certain microaggressions. For me, people have definitely made sacrifices to open doors, and I feel that it is my responsibility to step into those doors and open more doors for people that are coming behind by not just being Black in the space, but being authentically Black in that same space.”

As students like Griffin explore how the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement have reshaped the landscape of communication, journalism and public relations, USC Annenberg faculty have engaged with their students about how their industries of practice will address questions of racial equity when their students enter the workforce.

Rook Campbell, a lecturer in communication, sees the kinds of frank conversations we are having now about race in sports journalism as holding the potential for widespread, positive change in the profession.

“What I think has happened in the media is the shifting of thinking about who we are, and who’s constituted in that ‘we,’” Campbell said. “People in newsrooms are talking about positionality and what allyship looks like in this context. It does feel different than two years ago or five years ago.”

Campbell is also challenging students to take the lessons of famous athletes’ activism and apply them to sports in their own lives. “We need to ask these questions: ‘My swim team or volleyball team is all white — why is that?’” they said. “You look at surfers doing paddle-out memorials for George Floyd — are they aware that the beach they’re on used to be a segregated beach? The real power of athlete activism is when we start to have a collective reckoning, which will hopefully get us to collective healing and justice.”

Carrington notes that, in legacy news organizations, sports has often been viewed as separate from news and politics. If that was ever true, it certainly isn’t anymore. “Those of us trained in sports journalism are going to have to rethink how we engage with wider social issues,” he said. “Those issues are integral to sports and sports journalism. You can still be a sports journalist and not know about those issues. It’s just that you’re not going to be a very good one.”

Faculty have a responsibility to prepare students to be well-versed in issues of racial justice in the sports space, Carrington says. “At Annenberg, we’re matching professional practice with research — alongside deep, critical thinking about race in sports,” he said. “Professional sports makes big claims about its importance to society, that it constitutes a wider public good in our communities. That public good now has to include a critical understanding of questions like racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia. These organizations must be an active force for social good. They can no longer be passive in allowing inequality.”