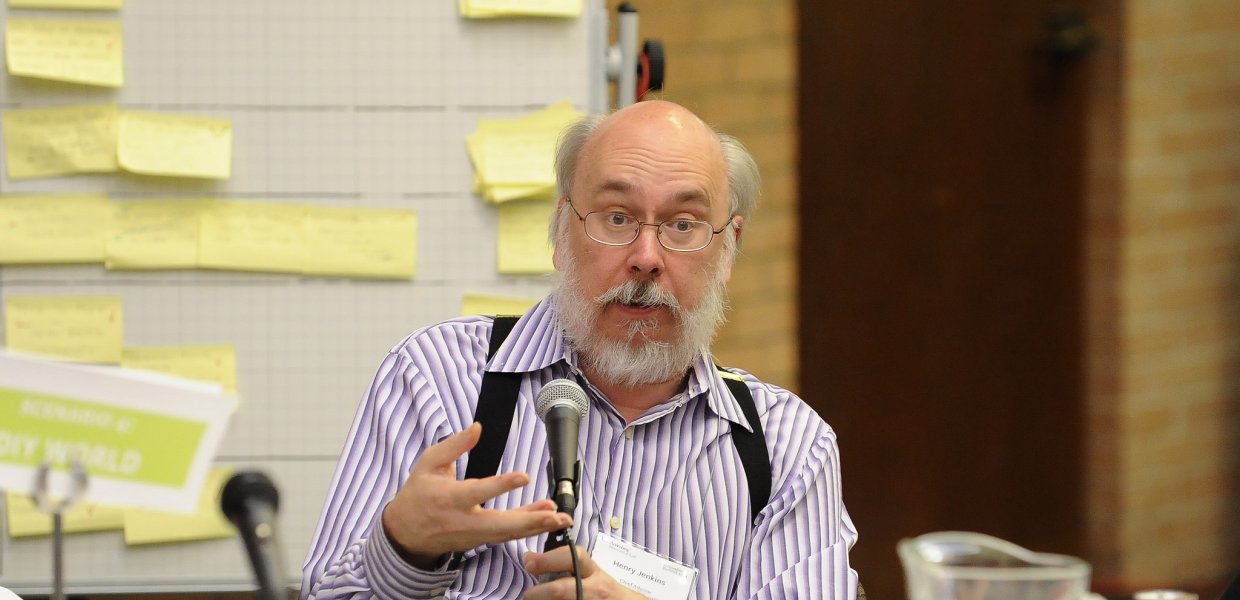

Inside USC Annenberg's classrooms, students are the ones typically tasked with answering the hard questions. "Five Minutes with..." turns the tables on faculty members by asking them the questions.

Henry Jenkins is the Provost's Professor of Communication, Journalism, Cinematic Arts and Education at USC. He is recognized as a leading thinker in the effort to redefine the role of journalism in the digital age. His work has focused on media consumers and participatory culture, which he defines as "a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices."

Jenkins describes himself an "Aca-Fan," a hybrid academic and a fan who tries to bridge the gap between those two worlds. A voracious consumer of popular culture himself, his research has involved observing fan experiences—of film, television, games, books—from a cultural studies perspective.

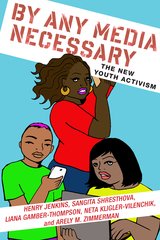

His latest book "By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism" examines how contemporary American youth are utilizing new forms of communication, like social media and viral memes, to fight social issues, dispelling the notion that they’re uninterested in politics and current affairs. The book provides case studies analyzing a wide variety of organizations and movements involving youth, including the Harry Potter Alliance, Invisible Children, and DREAMer movement.

His latest book "By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism" examines how contemporary American youth are utilizing new forms of communication, like social media and viral memes, to fight social issues, dispelling the notion that they’re uninterested in politics and current affairs. The book provides case studies analyzing a wide variety of organizations and movements involving youth, including the Harry Potter Alliance, Invisible Children, and DREAMer movement.

Jenkins shared a few thoughts with us about the book, participatory politics, Twitter revolutions, and the age-old battle between Star Wars and Star Trek fans.

What do you mean by "the new youth activism"?

I have been part of the MacArthur Research Network on Youth and Participatory Politics (YPP), and our book emerged from multidisciplinary conversations seeking to understand the political lives of young people today. My co-authors—Sangita Shresthova, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, Liana Gamber-Thompson, and Arely Zimmerman—were researchers and scholars affiliated with our Civic Paths research group here at USC.

Our book looks closely at five cases—Invisible Children and the Kony 2012 campaign, fan activism as embodied by the Harry Potter Alliance and Nerd Fighters, the DREAMer movement for the rights of undocumented youth, various cultural movements involving American Muslims, and young Libertarians. We could have discussed many others, especially Occupy Wall Street and #Blacklivesmatter, and perhaps even the Bernie Sanders campaign. We've identified a much broader range of examples through our digital archive, at byanymedia.org.

In each of these movements, young people play central roles—their participation is not simply an apprenticeship to adult leaders. They are not simply stuffing envelopes; they are often shaping the strategies, tactics, and messages of these movements. They are not treated as citizens in the making, but rather as already political agents who are making a difference in the world. In each of these cases, the mechanisms and infrastructure of what I call participatory culture get adopted and deployed by these movements in order to bring about social change. We call this participatory politics.

These movements have been innovative in their use of social media but they all represent efforts to change the world "by any media necessary"—that is, through tactics that deploy whatever communication resources they can access. Social media has in particular enabled them to circulate their messages through larger networks with limited opportunity costs. Often, these groups are seeking change through educational or cultural mechanisms as much as through institutional politics, reflecting a growing sense that American democratic institutions are busted. While it is urgent to repair that damaged system, some problems can't wait and changing people's hearts and minds can make a difference in how we treat each other.

Are there any examples of movements from the past that could not exist today? Or vice versa?

Malcolm Gladwell famously set up a contrast between the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and today's "Twitter revolutions." We think this contrast is problematic in many senses, starting with the fact that he is comparing a social movement with a media platform. We could talk about the civil rights movement as a long distance telephone revolution—the leaders spent a lot of time coordinating activities across geographic distances via the telephone—but we would never reduce that movement to a single platform. Rather, the civil rights movement used many different means to change people's thinking, and the same would be true of today's activists.

This is why we evoke Malcolm X when talking about change "by any media necessary" and the connections back to Malcolm X are clear. He shared a vision of social change which required his community to gain greater control over the means of media production and circulation and saw youth as a driver of those changes. So, we see lots of continuities with previous movements, but the new media environment opens up other possibilities—new communication channels—which expand the repertoire available to social movements.

That said, we do see some distinctions if we look at the traditional immigration reform movement and the DREAMers. The immigration reform movement has historically been more hierarchical, with messages controlled by select community leaders (especially ethnic media producers); the DREAMers have been much more broad-based and participatory, with young people often producing and sharing their own "coming out" videos via YouTube, other media sharing sites, and even in person. In many cases, these are the digital have-nots: young bloggers who do not own their own computers, young video makers who do not own their own cameras. They have been effective at coordinating their activities across geographic distances and cultural differences because of the networked structure of their organization. And they have made the process of change an everyday aspect of their lives via social media as opposed to a special event, such as a protest rally.

What role does social media play in youth activism? How do non-millennial activists view social media?

Young people get much of their information from social media, which means that news and political messages are integrated into their everyday interactions with their friends. While social media is one tool among many for today's social movements, it has a special status because it connects so immediately with people's everyday lives. Many young people complain that the language of politics is exclusive (in that it assumes a policy wonk already well informed about the political process) and repulsive (in that it reads every issue through partisan gamesmanship). The use of memes and remix videos, for example, spread through social media, allows young people to experiment with other languages through which to frame political messages. And these platforms are appropriate for the models of social change driving their campaigns—change that comes on a grassroots level, change that comes through educating people and shifting the culture rather than necessarily changing laws.

That said, researchers often find young people moving away from political speech on social media over time because of discomfort in bringing divisive issues into what is for them a core support mechanism. We hear more and more stories of people getting so fed up by the divisive political debates on Facebook this election cycle, that they are abandoning social media altogether, or conversely, choosing to keep their political opinions to themselves. So, as they say in Facebook-land, it's complicated.

Should an organization like the Harry Potter Alliance, deeply rooted in pop culture, be taken seriously when it comes to influencing policy?

Our research has led us more and more to focus on what we call the Civic Imagination. Imagination plays a range of functions in the process of political change. Before we can change the world, we have to be able to imagine what a better world looks like. We have to see ourselves as agents capable of making change. We have to see ourselves as connecting in powerful ways to a larger community. We often need empathy for people whose experiences differ from our own.

In different historical and cultural contexts, the civic imagination is inspired from different sources. For the American founding fathers, it was the ideal of democracy in the classical world. For the civil rights movement, it was the rhetoric of the black church and particularly the story of Moses. For many young people around the world, the civic imagination is being fed by stories appropriated and remixed from popular culture. We see activists are fighting for social justice using superheroes, the three finger salute from "Hunger Games," the Guy Fawkes mask from "V for Vendetta," and as of this summer, Pokemon Go. We've found this across all of the social movements we've considered, and as we expand our research for our next phase we increasingly believe that this is a global phenomenon.

The Harry Potter Alliance is a powerful example of the civic imagination at work—a large network of young activists working in support of human rights struggles while tapping the infrastructure and skills of the fan community. The practices which work to draw in young people who may not have seen themselves as "political" before may sometimes work to decrease the success of such groups when working within political institutions, but less so than you might think. These groups are forging partnerships with human rights organizations and NGOs, they are helping to shape the agendas of political debates, and they are drawing mainstream media coverage to their issues.

What's the role of entertainment in promoting social justice causes, such as the events put on by Invisible Children or, more recently, celebrities such as Leonardo DiCaprio's participation in the protest against building the Dakota Access Pipeline?

What you are describing here are examples of celebrity activism, which can be effective, especially at drawing mainstream media coverage to particular causes, and also sometimes in getting media to circulate broadly through the celebrity's network of fans and followers. Yet, the use of celebrities can often blunt the critical thrust of activist messages, since the celebrity will not want to put their professional lives at risk.

Such efforts are centralized and top-down, which make them the opposite of the kinds of decentralized and bottom-up political movements we discuss in our book. The before mentioned Harry Potter Alliance taps the power of a shared mythology, but does not depend on institutionalized gatekeepers. Indeed, the group has been willing to put its relationship with the commercial producers at risk, waging a four-year boycott of Warner Brothers, which controls the film rights to the Harry Potter series, to educate people about Fair Trade issues. Celebrity activism depends on the authorization provided by unique individuals, whereas fan activism is shaped by the public's ability to appropriate, remix, and recirculate stories from popular culture that they find meaningful.

Invisible Children interested us in part because of the ways it struggled with the tensions between a top-down celebrity activism model and a more grassroots and participatory model, with different priorities dominating their efforts at different stages in their process.

You've written extensively about science fiction fandom. Which would be more likely to bring about social change: Star Wars fans or Trekkies?

We can imagine political activism emerging from both fandoms, but they might take somewhat different shape. For my generation, Star Trek was very much a show about inclusion and acceptance of diversity. What diversity means has shifted through the years, but I've written about how GLBT activists have used Star Trek's promise of a more inclusive society to lobby for the inclusion of queer characters on the series. Star Trek fans have also rallied behind inclusion in terms of recruitment for NASA, a cause which Nichelle Nichols (Uhura) spent many years promoting.

Activism around Star Wars, on the other hand, has started from the notion of the Rebel Alliance, a metaphor which has been used by activists on both the Right and the Left. In the past year, I've seen Star Wars fans rally for campaign finance reform (battling against Dark Money as the Dark Side of the Force) and as a platform to celebrate teachers (because of the role of Obi-Wan and Yoda as mentor figures). But most pervasively, it has also in the past year been used to reflect on issues of inclusion, because of the growing diversity in its cast of characters.

Both offer us resources we can use to rally for social change, but doing so depends on matching the right metaphor to the right cause.