In 1998, USC Annenberg Professor Sandy Tolan was in Ramallah, Palestine, doing research for what would become his 2006 book, “The Lemon Tree.”

While there, he saw a poster featuring two pictures of a young man. One picture showed him as an 8-year-old, throwing a rock at an unseen Israeli soldier, while the other showed him as an 18-year-old, playing the viola. It was an advertisement for the Palestine National Conservatory of Music.

But Tolan also saw it as “an advertisement for this idea of putting down the stone and picking up a musical instrument and creating a peaceful nation, a sovereign nation at peace with Israel, which was the hope at the time.”

Tolan found the boy, Ramzi Aburedwan, in a refugee camp, where he lived with his grandparents.

“I asked him what his dream was and [Aburedwan] said, ‘Well, I want to open music schools for Palestinian Children so that they know there’s something besides a stone. They can have hope through music,’” Tolan recalled of their conversation, which he turned into a piece for National Public Radio.

Nearly 10 years later, the two ran into each other by chance in Ramallah. Since their last conversation, Aburedwan had received a scholarship to study music in France. He had returned to Palestine to build music schools, to do exactly what he told Tolan he’d do.

Tolan was inspired by Aburedwan’s persistence and spent the next few years documenting Aburedwan’s story and the impact his music has had on Palestinian people. Because of Aburedwan, hundreds of Palestinians are able to take music lessons every year.

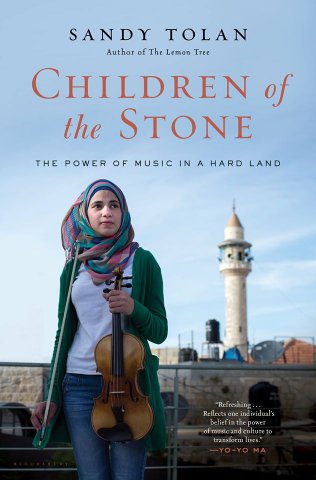

The book, “Children of the Stone: The Power of Music in a Hard Land,” was published — and discussed at USC Annenberg — on April 7, 2015.

The book, “Children of the Stone: The Power of Music in a Hard Land,” was published — and discussed at USC Annenberg — on April 7, 2015.

Tolan calls the book “a non-fiction novel.” He uses the story of Aburedwan — and his fellow Palestinian musicians — doing “something beautiful under grim and challenging circumstances” to engage readers, but also to get them to understand what life is truly like for Palestinian children under military occupation.

Most recently, however, Tolan and Aburedwan have been engaging readers in a much more intimate way. After the book's release in April, they set off on a promotional tour that integrated Tolan’s text and Aburedwan’s music, accompanied by the ensemble Aburedwan founded, Dal’ouna.

“The Children of the Stone/Dal’Ouna Tour is a musical and literary tour de force, bridging cultural divides by promoting cross-cultural sharing through the fusion of unique musical and literary works including Palestinian folk, world and classical music, jazz, combined with biographical narrative nonfiction,” according to the tour website.

“I would explain the book and tell the story, and then I would read a passage about how a kid was playing a particular song and [Aburedwan] would come on stage and play the song as I was doing the reading,” Tolan recalled.

They also often showed parts of a documentary called “Just Play,” which told Aburedwan’s story and featured an interview with Tolan.

The events took place in cities across the country, but Tolan said their visit to the National Cathedral in Washington D.C. was a highlight for him. The event took place in a small auditorium that was soon filled to capacity with people standing in the back and sitting in the aisles.

“They were just so receptive to the message of the book and the beauty of the music and the whole mélange of the East and West,” Tolan said.

The tour concluded on July 12 with a stop in Maryland — and an interview with Tolan and Aburedwan on NPR’s “Weekend Edition” — but Tolan said they hope to do additional tours in the future and continue to convey the message of the book and the power of Aburedwan’s story.

“I hope that the book is received as an opportunity to broaden and deepen and change the conversation in the U.S. about Israel and Palestine,” Tolan said. “I think we’ve been focused so much on the very legitimate question of how to keep Israel safe, but very infrequently does anyone say, ‘we need to keep Palestinians safe.’”

Even the simple act of learning music has proven difficult for Palestinian children under occupation. Tolan cited instances where children carrying an instrument case have been stopped at military checkpoints and forced to play music for soldiers.

“If people could see what day to day life is like for Palestinian kids, I think they would find that the story needs to be told more, the story of the occupation,” Tolan said. “And then we might begin to see some change.”

Watch Tolan discuss and read from his book:

Read an excerpt from Tolan's book, “Children of the Stone: The Power of Music in a Hard Land,” below:

Five young men stare through the windows of their bus, stalled at a military checkpoint known as Qalandia. Outside, an exhaust-choked border crossing divides Jerusalem from the West Bank city of Ramallah. Behind it stands a massive gray wall, seemingly impenetrable except by special permission. The men look out as drivers jockey for position, funneling into a single line before submitting for inspection. Vendors, mostly children, weave through the knots of vehicles, amid the plastic litter and chunks of broken concrete, selling kebab, tissue packets, pillows, bottles of water, and verses from the Qur’an.

Soldiers enter the bus, M-16s on their shoulders. A young woman inspects documents. She orders twenty people off the bus, including the five young men. They will not be allowed to cross the checkpoint in relative dignity, unlike the foreigners who remain on the air-conditioned coach. Instead, they walk through the heat into a trash-strewn terminal and pass down a long narrow corridor framed by silver bars. It looks like a cattle chute on a western American ranch. At the end the men push through two eight-foot-high turnstiles known as iron maidens. A stray cat straddles a wall above them. keep the terminal clean, a sign instructs.

The men crowd with dozens of others into a small holding area in front of a third floor-to-ceiling turnstile. Every few minutes a red light turns green, a click sounds, and three or four more people pass through the iron maiden to place their possessions on a conveyor belt. They hold up their permits to a dull green bulletproof window and look through the smoky glass, waiting. On the other side, bored-looking soldiers glance up, inspect the documents, and, one by one, wave the permit-holders through.

All but the five young men. “You do not have proper permits,” they are told.

Denied the Holy City, the men click their way backward through the gates, along the metal chute, and into the maze of cars and vendors, uncertain what to do next. It is urgent that they reunite with the others on the bus, so they can all reach Jerusalem.

“Hey, boys,” calls an unshaven man sitting on a stool inside a crude metal shed. The man takes a drag of his cigarette. He glances at the glass tumbler in his hand and the dregs of his Turkish coffee. The young men look behind him, toward the twenty-five-foot-high wall. They approach. Two of them carry long felt bags; another holds a blue canvas case.

The unshaven man takes a last drag of his cigarette, flicks it in the dirt, and looks up. “Ya, shabab,” he says, exhaling a long column of smoke. He smiles. “You boys need to get to Jerusalem?”

“Yes,” says the oldest of the five young men. He appears to be in his thirties: slim, of medium height, with a scraggly beard, a receding line of curly black hair, and bags under his eyes. His eyes are brown and unblinking, narrowed with intent. “It’s very important.”

The man sets down his glass, stands up, and regards the men in front of him. Except for the older one, they look a little nervous.

“For two hundred fifty shekels, I will get you to the middle of Jerusalem,” he boasts. “Fifty shekels each.” About fourteen dollars per man.

“Fine,” says the oldest of the five, who appears to be their leader. “What do we do?”

The man looks over his shoulder. “Jamal,” he says. “Get these guys to Jerusalem.”

They climb into a battered white van. The door slides shut and the driver begins working two phones, making arrangements. He drives with his forearms as the van rattles down a potholed access road. He turns to the men in the van: “Give me the money.” They haggle over price, finally agreeing on eleven dollars each. “But you have to pay now,” the driver says. He gives them his phone number and tells them to call once they reach Jerusalem. Apparently he wants satisfied customers.

A short time later the driver pulls over and steps into a tall garage made of corrugated metal. He returns with a ladder, extends it to its full length, and rests it against the top of the wall. He scales the ladder and sits beside it at the top. “Come,” he commands.

The men approach the base of the wall and look up, shifting their burdens from one shoulder to another.

They are classical musicians: a violinist, a violist, a double bass player, and two timpanists. Their felt bags contain sticks for concert timpani. The blue canvas case holds a violin. The rest of their orchestra is on the bus, rolling south toward Jerusalem. In four hours, they are due to play Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony in the Old City, at a French church built during Crusader times. Hundreds are expected to attend. If these five players don’t make it, the orchestra’s leader has warned, they will cancel the concert. It is impossible, after all, to play Beethoven’s Fourth without the timpani.

The musicians gaze to the top of the wall, where loops of razor wire present a dangerous obstacle. With a sweep of his arm, the smuggler brushes the loops of wire aside, like a curtain. The razor wire has already been cut. This is a regular crossing point.

The smuggler pulls a long knotted rope from a plastic bag, loops it around a metal post at the top of the wall, and drops it to the other side.

“Ta’al, ta’al,” he repeats. “Come.”

The violist goes first. He mounts the ladder rapidly, sits atop the wall, pivots his legs, grabs the rope, and slowly slides down. He tries to use the knots as footholds, but they are small and his feet keep slipping off.

A vehicle approaches on the narrow access road. The violist freezes about halfway down the rope.

“Who’s in that truck?” he shouts, craning his neck upward. “Are those soldiers?”

If they are, the violist will be arrested or, possibly, shot. It would not only mean he won’t get to Jerusalem for the Beethoven concert that evening. It could signal the end of everything he has been building for years.