Memes have become an inescapable part of our everyday communication. They usually appear on social media as combinations of images and clever captions, the best of which go viral on Twitter and overflow into our Facebook and Instagram feeds. One of the more popular memes is Grumpy Cat, whose classic turned-down mouth resembles a frown and is often coupled with cynical block text commenting on life. Quotes like “So many reasons to be grumpy, so little time,” or “I had fun once, it was awful,” sum up the sentiments of how the cat — and, by extension, the people who post the meme — are feeling.

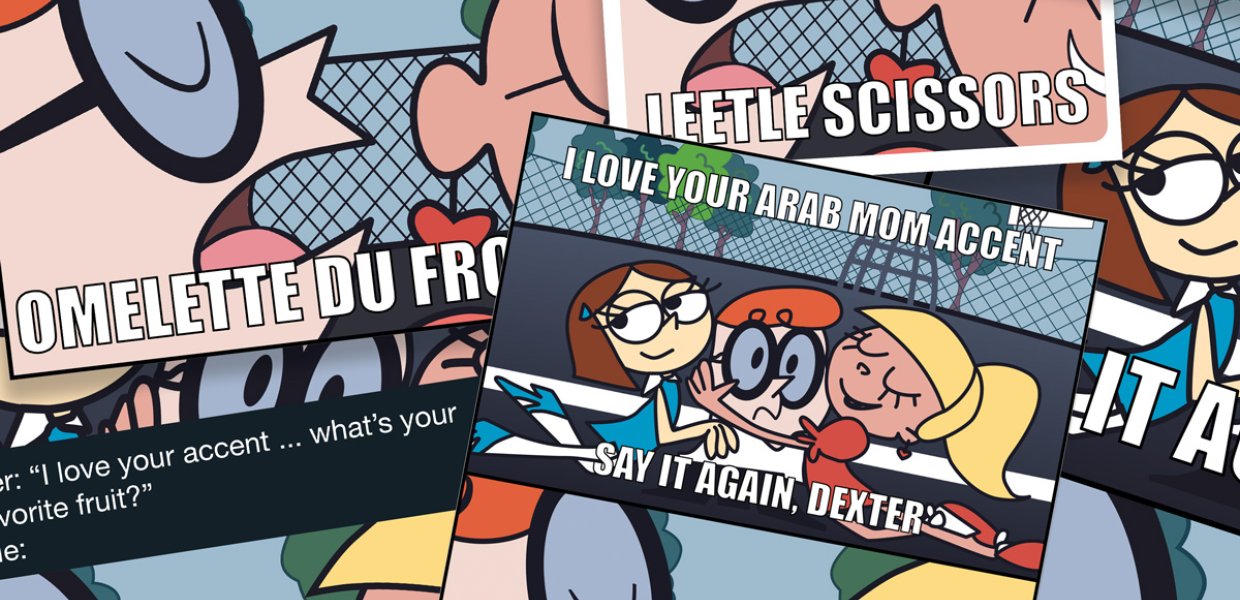

I had been studying memes for a few years when, in late 2018, a meme in a group chat of my Arabic-speaking friends caught my attention. The meme showed Dexter, the genius boy from Cartoon Network’s show Dexter’s Laboratory, whispering into the ear of a yellow-haired girl with a dangling heart earring, who looks enamored with what he has to say. The block caption “bikimbawder” is printed below the image. If you read the word out loud, it is a transliteration of how some primary Arabic-speakers might pronounce the English words “baking powder.”

Initially, I laughed. I’m an Arab-American and this caption reminded me of the people in my life who pronounce “baking powder” in this way. However, my laughter turned into discomfort as the researcher in me awakened.

I went back to study the original scene in the 1996 episode of the show, titled “The Big Cheese.” In it, Dexter is supposed to study for his French exam, but puts it off. At bedtime, he places a contraption on his head that allows him to learn French, via a tape, while he sleeps. The tape gets stuck on the phrase “Omelette du fromage” (which ironically is the wrong way to say cheese omelette), and those three words become the only phrase Dexter can say. At lunchtime, it lends Dexter special attention from girls at his school, who appear to enjoy his French accent — they beg him to “Say it again, Dexter.”

Over the next few months, the play on the “Say it again” meme appeared on social media with captions using stereotypical pronunciations in a variety of accents: Arabic, Spanish, French, Filipino, and Italian, among others. In addition to the “bikimbawder” example, there was another asking Dexter to reveal — in a Spanish-speaker’s accent — his favorite fruit. He answers: “estroberi.” The tension I felt between laughter and discomfort did not go away. I decided to dig deeper to see how people are using memes to reflect, reinforce or disrupt certain values and power relations in American society as they relate to immigrants and accents.

I realized that the source of tension is in the ambiguity of its interpretation. The phrases in different languages are received with great enjoyment by Dexter’s female listeners. However, both Dexter’s accent and the reader’s enjoyment of it can be interpreted as either celebratory or belittling.

In the context of the often stereotypical portrayal of immigrant people in mainstream U.S. media, one way to look at this meme is as a reclamation of one’s pride in their culture and accent. In other words, celebratory. The meme is passed along primarily by people who speak or understand the accents cited in it. They express a shared meaning around the accent and the fact that only they can understand the intent.

While this might be part of what the meme represents, we should take a careful look at what is also embedded in this reclamation in terms of power dynamics: The meme presents these accents in a way that could be read as objectifying and belittling. By emphasizing the cuteness and exoticness of the accent, the meme can come across as patronizing, and render the person speaking as objectified, belittled and “othered.”

In other words, while those sharing the meme might not intend to mock Arab aunties for mispronouncing baking powder, they are still presented as objects of cuteness rather than people with social agency who are equally able to speak, to be heard and to make an impact on society. What it lacks is the necessary call to be seen as equal in the cultural hierarchy, a call that says, “This is my accent, and it does not make me inferior to anyone.”

As for me, I have not stopped purposely mispronouncing words like “bikimbawder” when I speak Arabic with my friends — I like that it can cause a laugh and create an atmosphere of bonding around shared meaning. But working on this study has made me more self-conscious in my language choices, and I now welcome this tension that comes with affectionate mispronunciation. I see it as a reminder of how complex the relationship is between my language choices and my place in society.