The wide-reaching impact of investigative journalism was on full display USC Annenberg presented the 2016 Selden Ring Award for Investigative Reporting on Friday, April 15.

Dozens of journalists and USC Annenberg students attended the ceremony at Wallis Annenberg Hall to honor the year's winning investigation, The Associated Press' “Seafood from Slaves,” a series compiled over more than a year by the multinational reporting team of Esther Htusan, Margie Mason, Robin McDowell and Martha Mendoza.

“Seafood from Slaves” delved into the $7 billion-a-year Thai seafood export industry, which the AP investigation proved relies in part on thousands of slave workers lured away from their home countries and held captive for years on remote islands in deplorable conditions. The AP team's reporting connected slave-caught seafood to Asian and European markets as well as American suppliers, restaurants and grocery stores such as WalMart, Target, Whole Foods and Red Lobster.

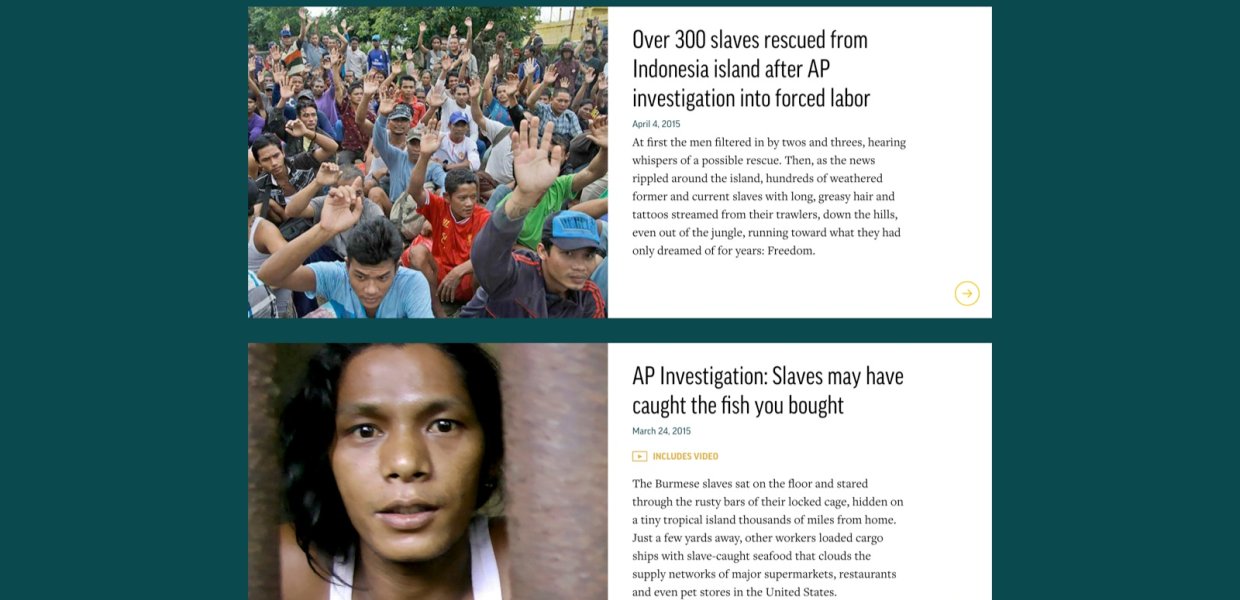

Over the past year, the investigation brought about legal action in multiple countries and ultimately resulted in the rescue of more than 2,000 formerly enslaved workers.

The series landed several investigative reporting awards; on April 18, the work was anointed with a Pulitzer Prize for public service.

“The impact of the reporting was swift and extensive,” School of Journalism Director Willow Bay said at Friday’s ceremony. “Their work is the kind of deep, meaningful investigative reporting with powerful impact that is the hallmark of the Selden Ring Award.”

“Seafood from Slaves” was selected to receive the $35,000 Selden Ring Award in February from among more than 80 other entrants. Established in 1989 by Southern California businessman and philanthropist Selden Ring, the award has been presented annually by the USC Annenberg School of Journalism in recognition of exemplary investigative journalism that has a substantial societal impact.

“I'm really pleased that this award exists, and that these stories are told,” said Cindy Miscikowski, CEO of the Ring Group. "Journalism, and investigative journalism in particular, have an impact that is really such an important foundation of our country.”

The Associated Press team began its investigation into the Southeast Asian fishing industry in late 2013 after Mason, the AP’s Indonesian Bureau Chief, received a tip from a source about Burmese workers being used by Thai companies operating in the area. Despite the substantial time and money the team knew the reporting would require, they agreed they had a moral responsibility to definitively investigate the allegations.

“For those of us living in Southeast Asia, this story was really an open secret,” said McDowell, who is based in Myanmar. “We all knew that the Thai fishing industry was using slaves and forced labor, but proving it was another matter.”

In order to find evidence that slave-caught seafood was being exported by Thai companies, Htusan and McDowell visited the remote Indonesian island of Benjina where they encountered thousands of Burmese slaves. They had been given fake Thai documents in order to work and were being kept there against their will.

On Benjina, the reporters found men locked in cages, who said they were often beaten and had not seen their families in years or even decades. Many were reluctant to talk to anyone except Htusan, who is Burmese.

“When Esther showed up, the doors flew wide open,” McDowell said. “To see someone that they knew was from their country, and who was going to tell their story to the outside world, made it almost impossible for them not to speak.”

Once the reporters saw the slave-caught seafood loaded onto ships leaving Benjina, they used satellite tracking to follow the cargo to cold storage and processing plants in a Thai seaport, where they hid from the so-called fish mafia in the backs of pickup trucks for four nights. After concluding that slave-caught seafood was indeed being exported abroad, Mendoza, an AP National Writer based in California, used public U.S. customs records to tie the shipments to American suppliers.

Prior to the publication of the original article in March 2015, the AP team worked with the International Organization for Migration to ensure the safety of the workers they named and interviewed in their reporting.

“They were incredibly brave to want to speak to us,” McDowell said. “They wanted the message out, and by not using their names and faces we would have really severely stripped the power of the story.”

Within weeks of publishing the first “Seafood from Slaves” investigation, the AP team was invited to join the Indonesian government as it conducted its own investigation in Benjina. Upon arriving and seeing the conditions of the workers, the government immediately rescued hundreds of workers, and over the next six months, more than 2,000 former slaves were freed. The AP documented the harrowing rescues in a follow-up article and video following the homecoming of one Burmese man who had been held captive in Benjina for 22 years.

The AP team's investigation brought about substantial legal ramifications, as well. At least nine people involved in the operation were arrested, and the U.S. State Department cited the AP reporting in its decision to keep Thailand on a blacklist of nations not doing enough to stop human trafficking. The investigation also prompted the Obama administration to call on seafood exporters to reform labor practices.

The team’s findings were also discussed during congressional hearings in which lawmakers argued an existing law barred slave-produced goods from entering the United States. The AP team found, however, that the law allowed for slave-produced goods to be imported if there is “consumptive demand,” and the loophole was subsequently closed by President Obama last month.

After discussing the process of reporting “Seafood from Slaves,” the AP team became the interviewees as students from investigative reporting classes led by adjunct journalism professors Gary Cohn and David Medzerian were able to ask the team questions about their experience.

Many students wondered about the place of longform journalism in the modern media landscape.

“We live in a 'TL;DR' generation, too long, didn't read,” USC Annenberg graduate student Mariyam Alavi said. “Do you think we still have the space for longform investigative journalism?”

For the AP team, the response was a resounding yes.

“There is space for longform journalism,” Mendoza said. “Some of our very long stories do very well. It's a matter of becoming better writers.”

Many students, including broadcast and digital journalism senior Crystal Goss, were curious as to whether the reporters anticipated that their work would have such an impact.

“We didn't expect to find a slave island, or to have all these major rescues,” McDowell said. “When the rescues started, there were many times when it felt like, 'Okay, this should be enough.' But I think none of us felt like that was enough. Things were still operating as they always had.”

For Mendoza, the ability to point to tangible, real-world results doesn't just makes the hard work of investigative journalism worthwhile. It's what makes future reporting possible.

“Journalism does not happen in a vacuum. The four of us worked a lot on this but so did everybody at The Associated Press,” Mendoza said during the ceremony. “We really appreciate this recognition, it helps us get traction when we're making the case to do more of this type of work.”

Video: Miami Herald reporters and 2015 Selden Ring winners, Carol Marbin Miller and Audra Burch speak about the judging process for the Selden Ring Award along with New York Times Assistant Managing Editor Rebecca Corbett. Miller and Burch also speak about what it's like to perform the deep dive of investigative journalism.